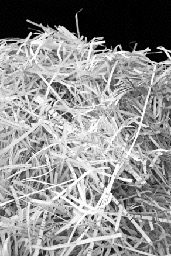

Bioinformatics applies programming and statistics to better understand biology. I first became interested in bioinformatics when in 2003 the Human Genome Project had just sequenced the three billion nucleotides of the human genome. A genome sequencing machine is much like a scanner for scanning paper documents. It would ideally scan entire pages at a time, or even entire books. An ideal genome sequencing machine would sequence an entire chromosome of DNA from beginning to end, but that’s not possible with current technology. Instead it’s as though a hundred copies of the book have been shredded into ribbons and then scanned. Those pieces then have to be reassembled to reconstruct the original book. Also, those pieces of paper have been given to a toddler to scribble on. Sequencing machines are not perfect and often make errors. I design computer software that reassembles shredded pieces of sequenced DNA to reconstruct the original genome sequence.

The genomes of conifers, evergreen trees, are four to ten times as large as the human genome. Their size makes assembling their genomes quite a challenge. I developed two software tools during my PhD. The first tool, named ABySS 2, reduced the memory requirements to assemble a genome by ten fold compared to contemporary tools. Whereas previously a large cluster of computers would be needed to assemble a genome of this size, this improvement made it possible to assemble a conifer genome using a single computer. Similarly, a human genome previously needed over four hundred gigabytes of RAM to assemble, and with ABySS 2 it needs less than forty, a ten fold improvement. That efficiency makes it possible to assemble not just a single genome, but an entire population of genomes, like the five million genomes project of Genomics England, which aims to sequence the genomes of five million people in five years.

One aspect of my research that I enjoy is that genome sequencing technology is constantly evolving, much like the genomes they sequence. New bioinformatics methods need to be developed to take advantage of each new sequencing technology, like a recently developed sequencing technology called linked read sequencing from a company 10x Genomics. Using our shredded book metaphor, it’s as though the front of each page has text on it, but the back of each page has been painted with a solid colour, before being shredded. That makes assembling the pages easier, because pieces from the same page should all have the same colour on the back.

The second software tool that I developed, named Tigmint, uses linked reads to identify errors in an assembled genome, like looking for assembled pages that have a mosaic of colours on the back. Tigmint cuts up those misassembled pages, and puts them back together correctly, so that the colours match.

I used these two software tools that I developed to assemble the genome of western redcedar, a very large tree native to the Pacific Northwest that can live over a thousand years. My research is used in selective breeding programs to breed naturally stronger trees, trees that are more resistant to insects, like the mountain pine beetle, and more adaptable to climate change, to ensure that our forests remain healthy and strong for generations.